Web Cache Poisoning via Parameter Cloaking

During a bug bounty session with @giacomozorzin, we discovered a Web Cache Poisoning vulnerability on a target leveraging Fastly CDN. Our analysis focused on the application’s search functionality, and in this blog post I’ll walk through how a simple XSS gains a much broader impact when escalated through a Cache Poisoning vulnerability, ultimately affecting all users that search for a specific item within the application.

Introduction

A web cache enables the static and rapid retrieval of content in modern web applications. By temporarily storing responses closer to end-users, caching significantly reduces server load, latency, and bandwidth consumption. Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) extend this principle at a global scale, distributing cached assets across geographically diverse edge servers to ensure speed and resilience.Web Cache Poisoning is a vulnerability that takes advantage of how web servers and CDNs handle cached content, allowing an attacker to store a malicious response in the cache so that it is later delivered to unsuspecting users, effectively turning a single request into a large-scale attack vector.

Specifically, Parameter Cloaking is a Web Cache Poisoning technique that exploits parsing discrepancies between a cache/CDN and an origin server; by embedding malicious input inside a parameter that the cache excludes from its cache key, but which the origin interprets differently (for example due to inconsistent handling of delimiters like ? or &), an attacker can “cloak” arbitrary parameters so they affect the application’s logic without altering the cache key.

Technical detail

During testing on our target, a well-known online retail site, we discovered a reflected Cross‑Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability in the search functionality of the application. User input from the search form was insecurely reflected in the page response without proper input validation or sanitization, allowing arbitrary JavaScript to be executed. For example:

/search/?q=input"><script>alert(0)</script>

So, by inducing a user to visit https://[REDACTED]/search/?q=input"><script>alert(0)</script> it’s possible to trigger the classic alert in the user’s browser.

After identifying the XSS, we pushed on with further analysis to uncover additional attack vectors that could amplify the impact; because, let’s be honest, a lone demonstrative XSS doesn’t exactly win you top-dollar bounties.

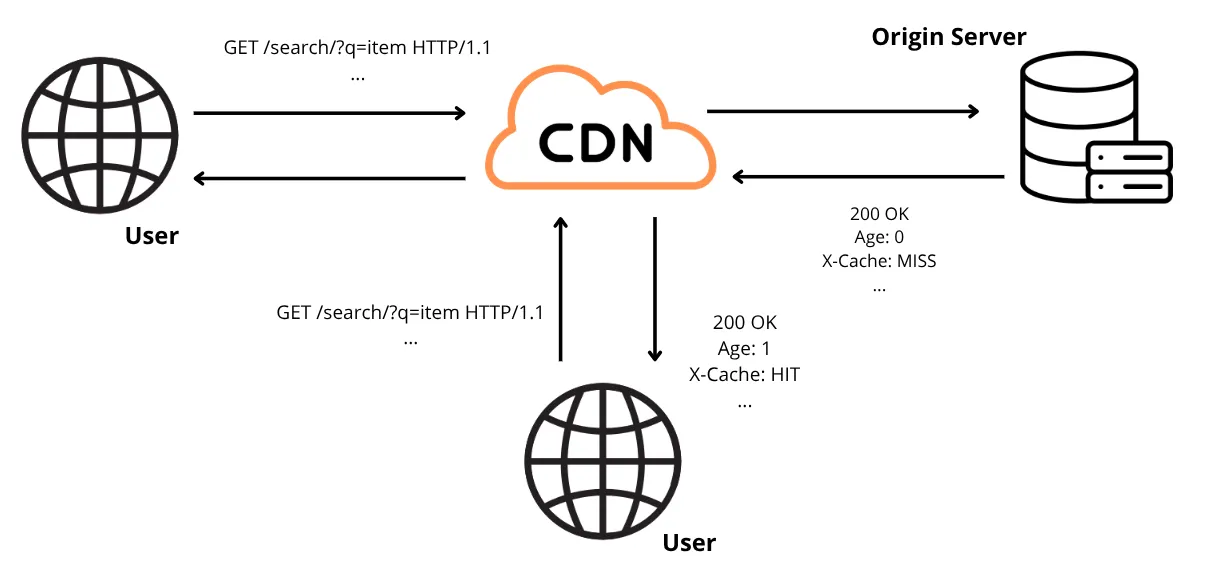

During our analysis, we found that the application relies on Fastly as its primary CDN and caching layer, and that all user search queries are being stored within it.

In particular, responses from the search functionality are cached using the q parameter as part of the cache key. This means that when a user searches for a specific item (e.g., q=item), the server’s response is stored in Fastly’s cache. All subsequent searches for the same value (q=item) are then served directly from the cache, bypassing the origin server.

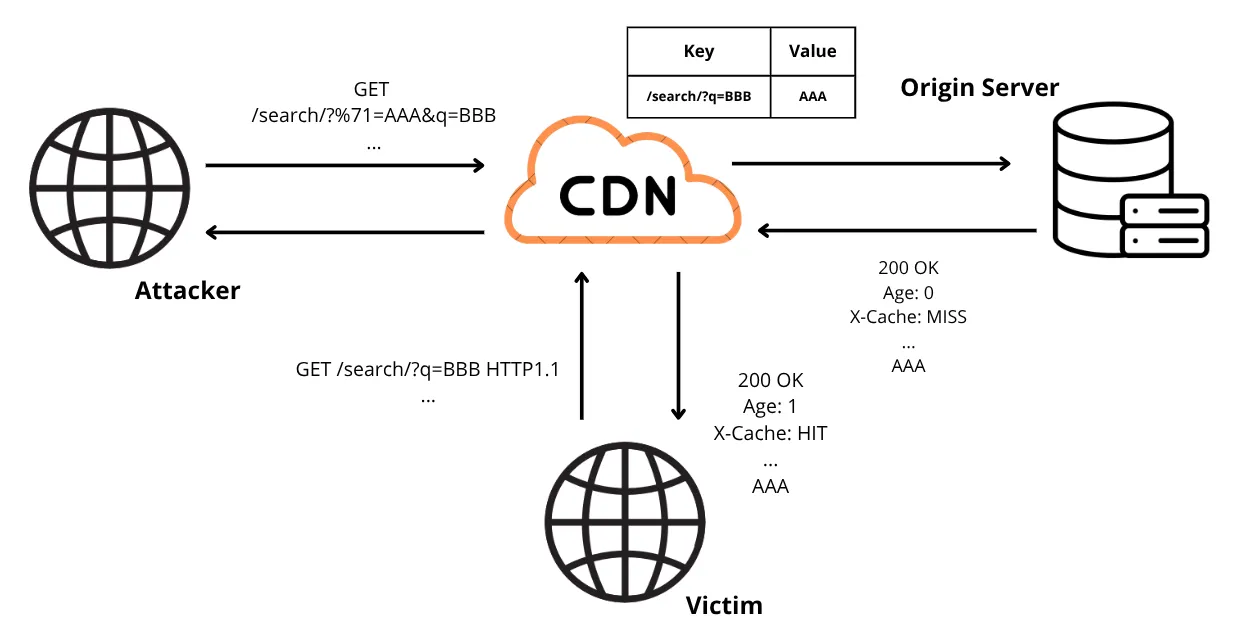

Digging deeper into the analysis, we observed that when two

q parameters are included in the request, the backend server processes only the first parameter, ignoring the second.

Because the application uses Fastly, which does not perform URL normalization before generating the cache key, sending two

q parameters and URL encoding the first, leads to the following interesting behavior:

-

The backend server, which performs URL decoding of incoming requests, processes the first

qvalue. -

Fastly cache server does not recognize the URL encoded parameter, thus the response will be cached using only the non URL encoded

qparameter in the cache key.

This discrepancy allows an attacker to poison a legitimate search by sending a request like the following:

/search/?%71=AAA&q=BBB

In this case, the response contains the search results for the term AAA, but the response is cached using BBB as the cache key.

When the victim performs a search for the term BBB, they will receive the poisoned cache response containing the result for the search term AAA.

Based on this, we can identify the following potential impacts and scenarios:

-

Denial of search functionality: an attacker could flood the cache with poisoned responses generated from non-existent search terms but stored under legitimate ones. As a result, when users search for a real product, they would be shown “item not found,” even though the item is actually available.

-

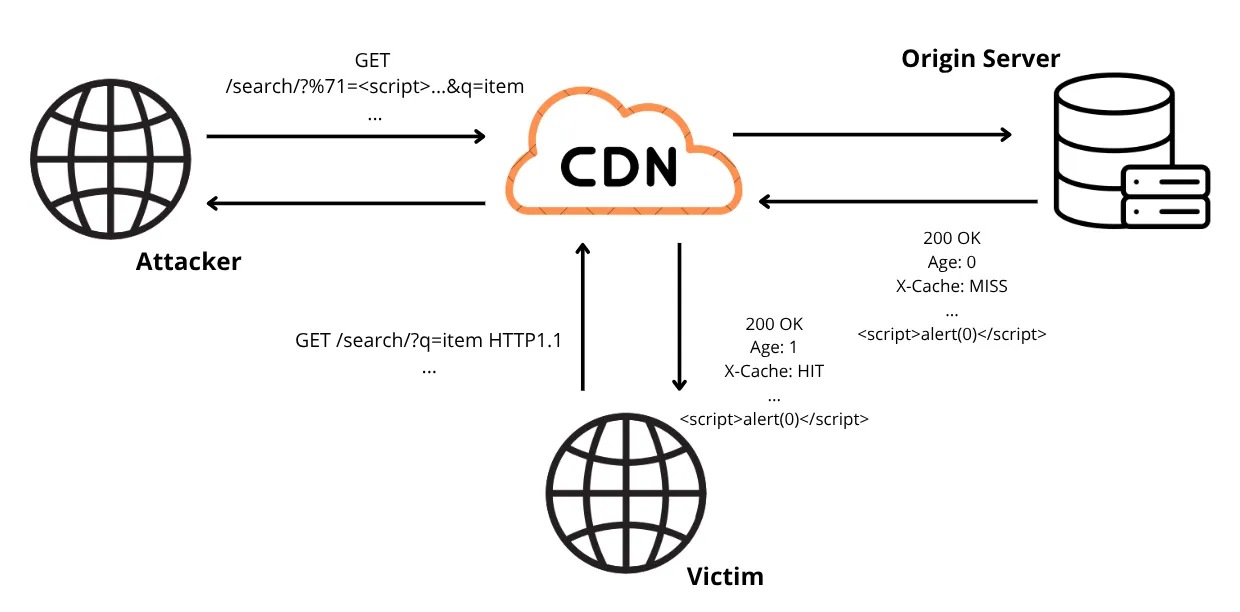

Large-scale XSS attacks: by chaining this issue with the existing reflected XSS in the search functionality, an attacker could poison cached responses with malicious scripts. Because the payload is cached at the edge, every user, authenticated or not, who requests the poisoned search term can receive and execute that script.

The practical impacts of a cached XSS are severe and diverse: stolen session cookies or authentication tokens (leading to account takeover), credential harvesting via fake login prompts or overlays, request forgery (the victim’s browser making requests on the attacker’s behalf), persistent keylogging or form-data exfiltration, automatic redirects to phishing domains, and drive-by downloads of malicious resources. When these actions are delivered from the CDN cache, a single poisoned entry can scale an attack to a large fraction of the user base almost instantly.

In plain language: cached XSS = XSS everywhere. By tampering with high-traffic search terms (for example, popular product tags or categories), an attacker can associate malicious responses with legitimate queries and have those responses served directly from cache to countless users.

As shown in the image above, the attacker repeatedly issues a crafted request where the first q parameter (URL encoded) carries a malicious payload and a second q parameter holds the legitimate search term used as the cache key. Example:

/search/?%71=<script>alert(0)</script>&q=term

A victim who later performs a normal search for term:

/search/?q=term

will receive the cached, poisoned response containing the injected payload, causing the script to execute in the user’s browser.

Below is a real example from our tests that demonstrates one of the possible impact: an attacker could poison the search term Poison, forge a response showing a phishing page, and trick the user into visiting a malicious website.

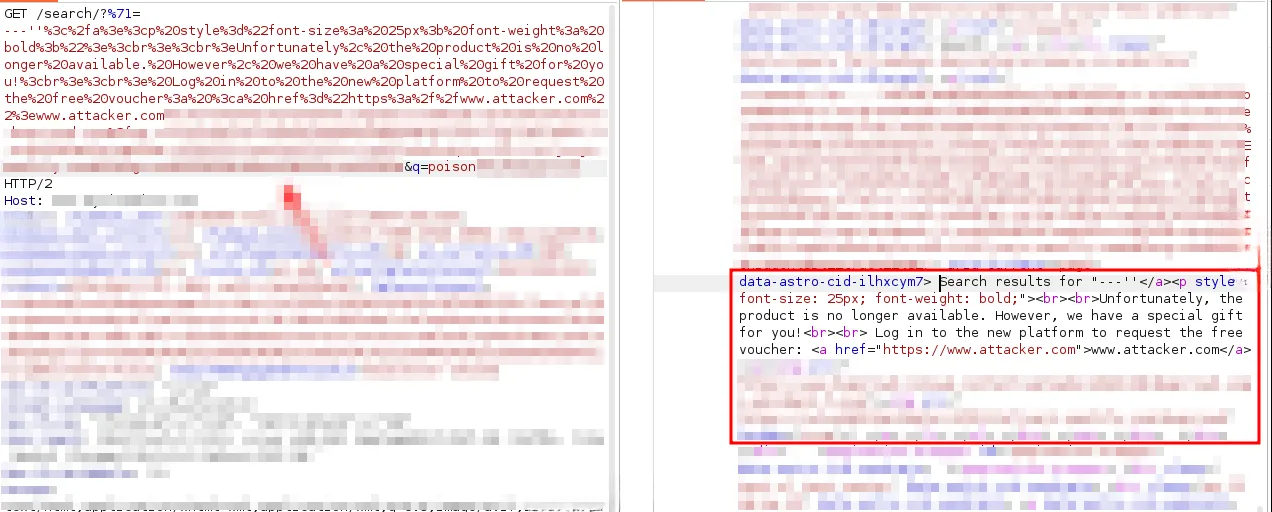

Below is the attacker request to poison the term Poison with the content included in the URL encoded q (%71) parameter. The injected payload is a basic HTML snippet that renders a deceptive message.

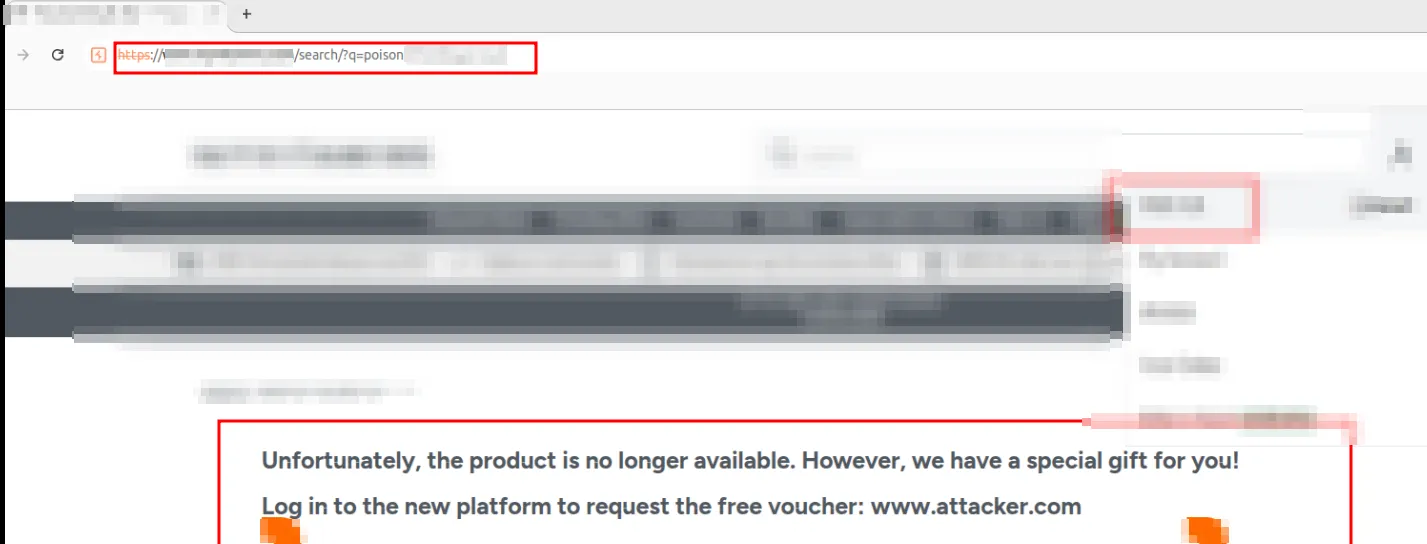

As shown in the image below, once the user searches for the poisoned term, the response returned contains the malicious text crafted by the attacker. It is also worth noting that the server’s response is served from the caching system, as indicated by the

X-Cache header set to HIT and the response’s Age value.

Conclusion

During testing, we discovered alternative methods and payloads to exploit the search functionality. We can’t publish full technical details yet because the vendor is still deploying the necessary fixes; consequently, this post includes only a partial proof-of-concept and intentionally omits any reference to the original issue while remediation is ongoing.

To conclude: the findings highlight why assumptions should be avoided; what seems like a minor vulnerability, for example ‘just an XSS’, can, upon deeper analysis, reveal significant impact.

Reference:

https://portswigger.net/research/web-cache-entanglement

https://youst.in/posts/cache-poisoning-at-scale/